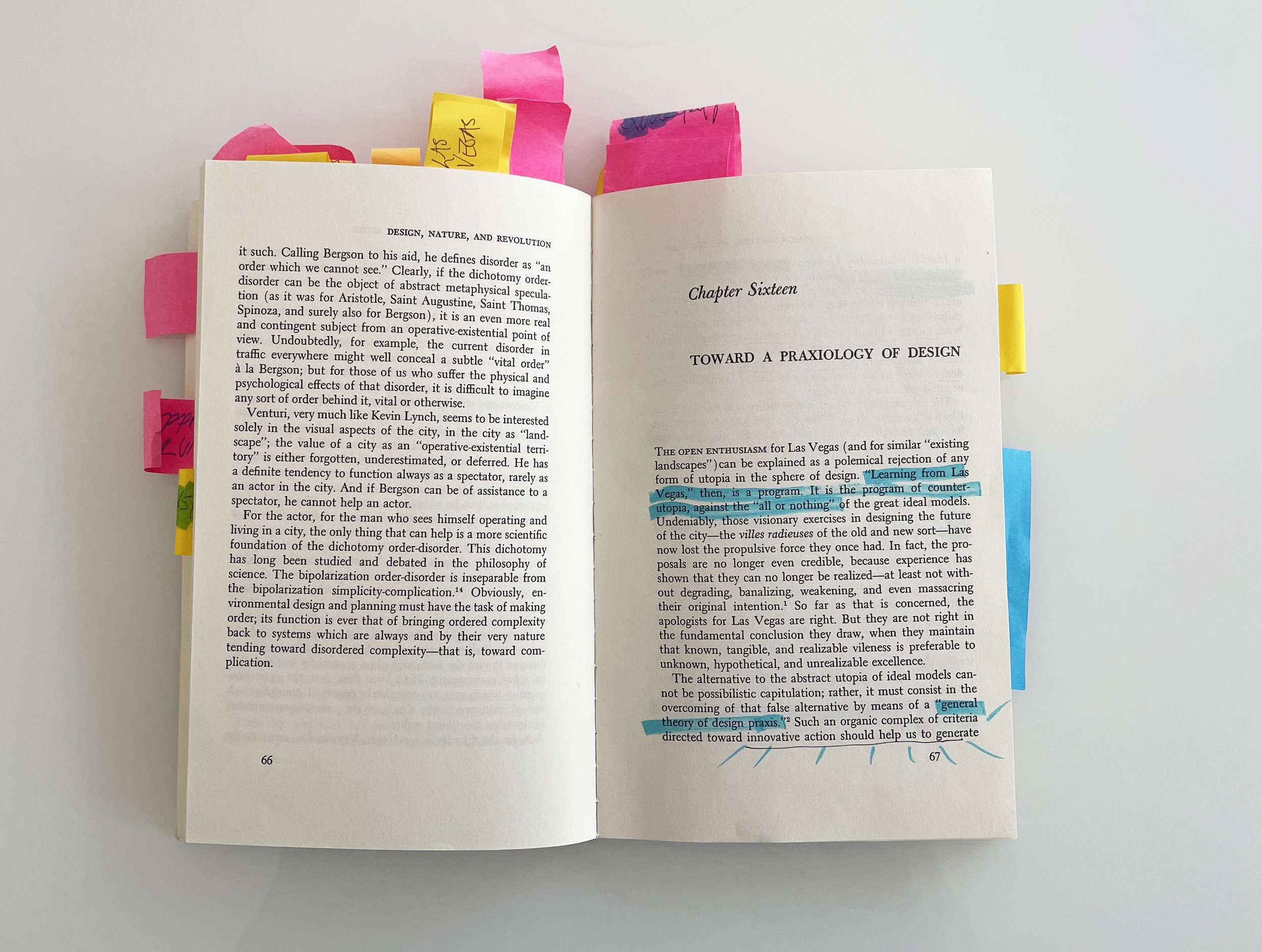

BOOK REVIEW“Design, Nature, & Revolution, Toward a Critical Ecology” by Tomás Maldonado.

Translated and edited by Mario Domandi, forward by Larry Busbea

https://doi.org/10.1080/17547075.2021.1975965

Tomás Maldonado’s book; “Design, Nature, and Revolution, Toward a Critical Ecology”; is a significant polemic that urges a reckoning with human impact on the environment. Written in Italian over half a century ago, long before the topic was omnipresent, the text is a philosophical observation of the impossibilities and the challenges of balancing human appetite for making, complex systems, the fragile nature of the environment, and the near impossibility of harmonious alignment. An Argentine designer, painter, and critical thinker, Maldonado’s academic tenure included positions at the Ulm School of Design in Germany where he helped to develop new systems-thinking in design education, Princeton School of Architecture, and the University of Bologna in Italy. A reprint of the 1972 English translation, Maldonado’s 77 page book—he called it an essay—is filled with philosophical inquiry into designs relationship in our environment. 50 pages of notes and sources show how thoroughly Maldonado’s positions are informed by the work of other critical thinkers, including German philosophers Karl Marx and T.W. Adorno.

When Maldonado talks about environment, he is referring not only to the natural world (or “ecological environment,” as he terms it), but also what he calls our “artifact-environment”—our constructed environment of buildings, systems, technology, and culture. In chapter one, “Environment, Nature, Alienation”, Maldonado touches on how the human artifact environment is dependent upon our use (or misuse) of the ecological environment and design systems. He looks backward to Aristotle, Nietzsche, and Freud to define man’s relationship with nature to conclude that the human world is our own making. In chapter two, “Human Ecology and Dialectic of the Concrete”, he explores human relationships with what he calls “concrete projection”—human desire for physical manifestations of our existence and our relationship to objects. For Maldonado our relationship with objects is one of correspondence; human-made artifacts impact the human condition now and in the future. Maldonado goes on to describe what he refers to as a “crisis of hope in planning”, which he says is fueled by an exploding population and nihilistic consumerism that together create a sea of waste, discards, and pollution.

Maldonado highlights megastructuralist Buckminster Fuller’s call for a revolution of design that takes aim at aligning technical structures and management of natural resources thus eliminating the need for war or politics. Maldonado finds Fuller’s ideas inspirational, although criticizes the lack of actionable steps towards executing this plan. Subsequent chapters explore the complexity of social and ecological systems, the challenges of attaining true innovation, and the semiological abuse of Las Vegas.

In the final chapter “Toward a Praxiology of Design”, he touches on the possibility of hope through design. He suggests that if we are to be innovative it must be through a balance of critical design consciousness—a symbiotic relationship between function and design praxis within the framework of capitalism. He critiques Ernst Bloch’s concrete utopia, a blend of speculation and technical realization, as inoperable theory, and in its place prioritizes an emphasis on technical processuality; procedures, actions, and logistical plausibility. According to Maldonado, the debate between design and revolution cannot be used as an excuse to put off application of strategic design and planning on a massive scale. He argues that our destiny may depend on this and it is the designer that must act.

At the book’s beginning, Maldonado warns the reader that the text is fragmented and erratic. But his analysis of design’s relationship to large scale systems, ecology, social structure, politics, and technology does important work to show the centrality of design for environment. While sustainable designers today are familiar with the visionary work of Victor Papanek, who wrote “Design for the Real World: Human Ecology and Social Change”, his now-classic text, two years after “Design, Nature, and Revolution”, Maldonado’s book has been largely overlooked. This reprinting seeks to rectify this by showing us how we still have a lot to learn and much to remember about design’s role beyond stylization of individual objects.

Maldonado is both a skeptic and a realist. He sees the complex relationships of systems, understands man’s proclivity for concrete manifestation, and envisions hope in the form of design and planning. Maldonado’s book, remains a rallying cry to defuse the inevitable apocalypse that exists in our relationship with our physical environment by leading with design and planning, for what is “a future devoid so of future” (75).